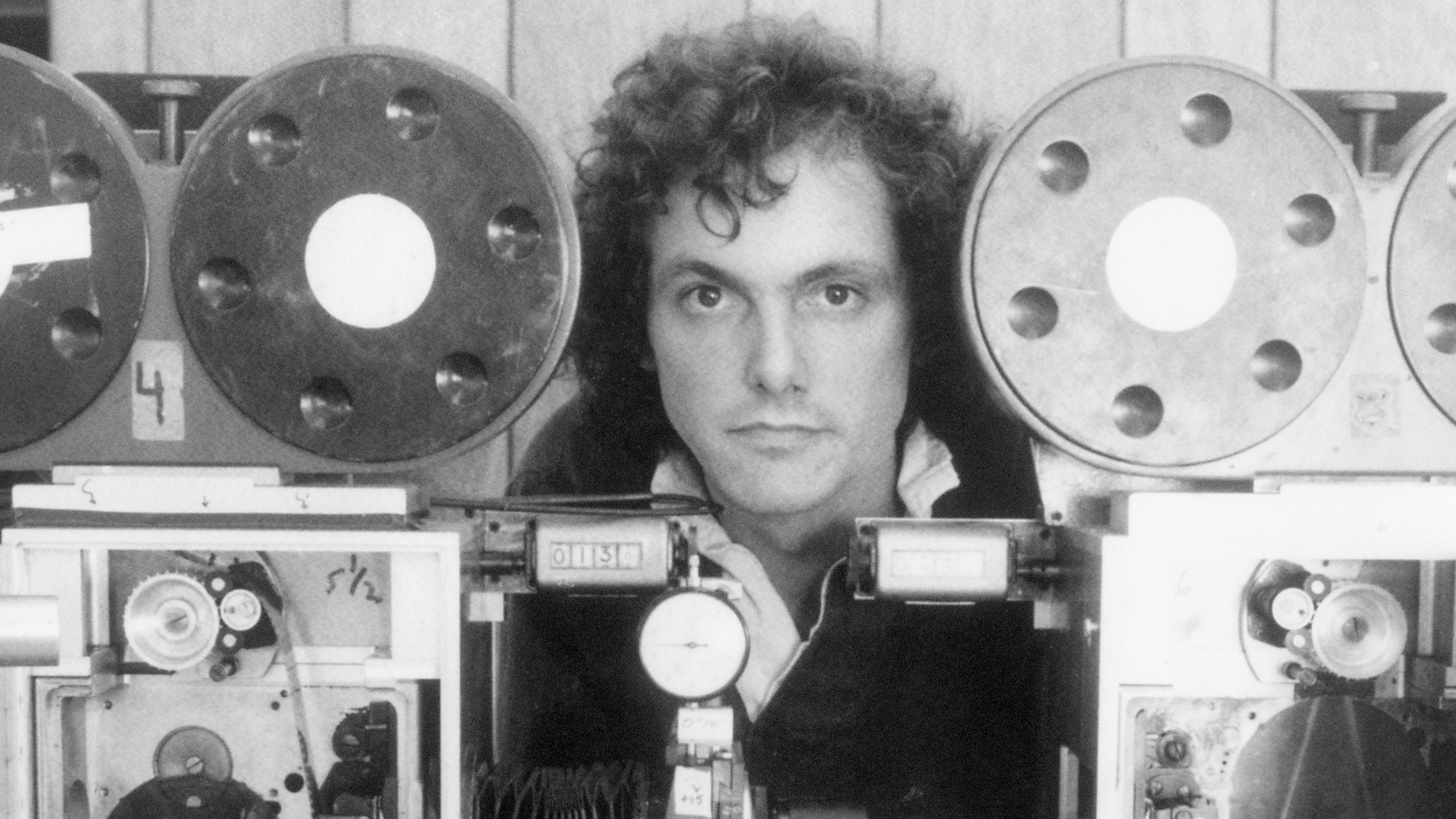

An Innovative Spirit: Robert Blalack, 1948-2022

Remembering a Key Figure Behind the Creation of Star Wars

One of the seminal figures in the establishment of Industrial Light & Magic, Robert Blalack passed away on February 2 at the age of 73. Everyone at Lucasfilm mourns his passing, and joins the industry in celebrating his contributions to the craft of visual effects and filmmaking. Our hearts go out to Mr. Blalack’s family and the entire visual effects community.

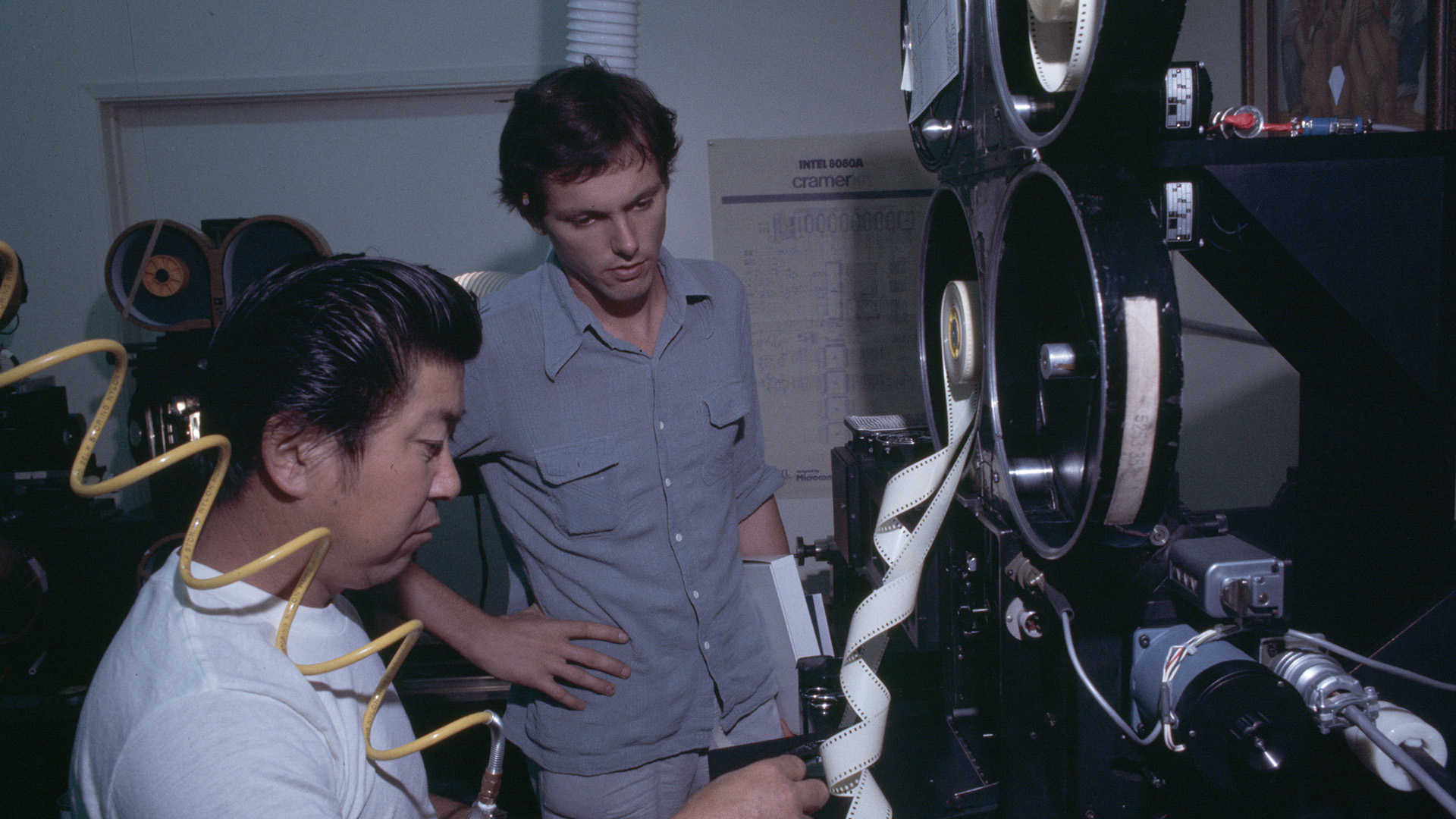

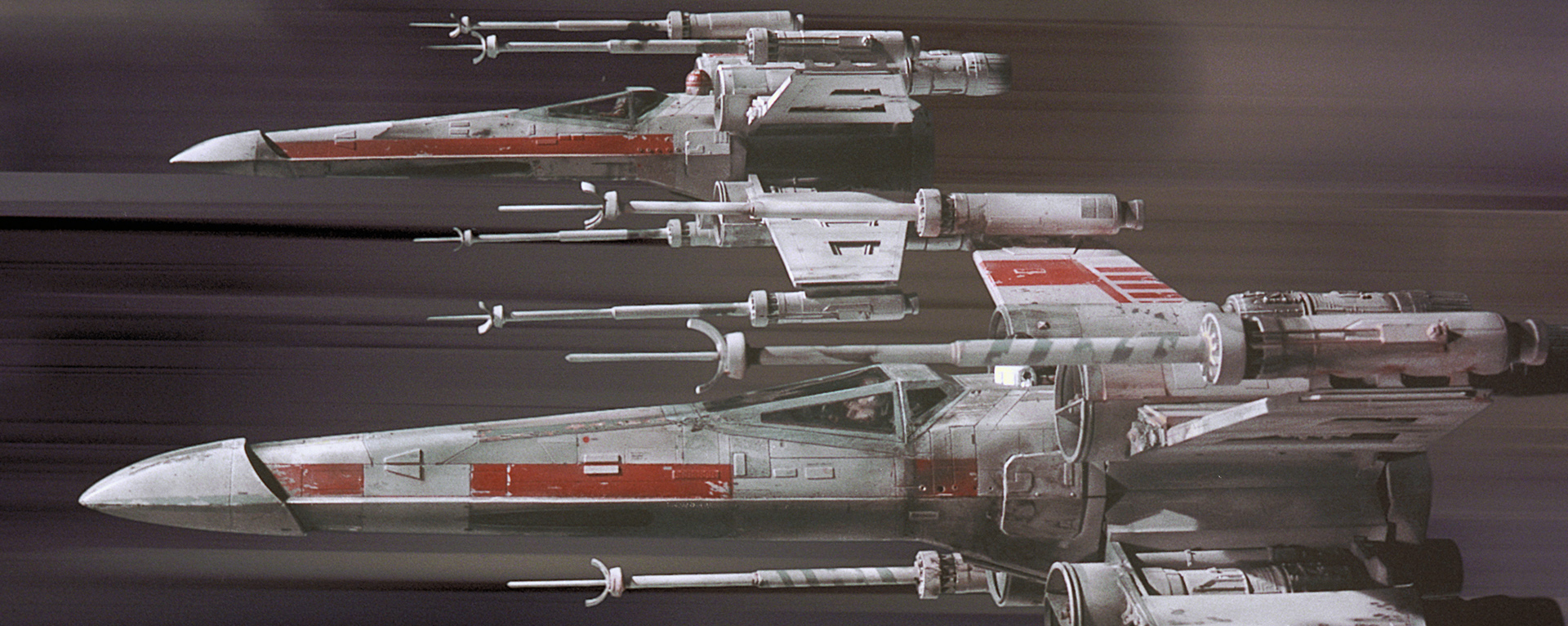

As the supervisor for composite optical photography on Star Wars: A New Hope (1977), Blalack was responsible for establishing ILM’s first optical department in Van Nuys, California, including the acquisition of cameras and optical printers for the compositing of visual effects shots. By piecing together separate film elements of starships and laser blasts photographed by the ILM crews, these tools actually made the effects audiences would glimpse onscreen.

Among these tools was Blalack’s own customized Praxis Printer and the historic Howard Anderson Optical Printer, the latter originally built at Paramount Studios and now on private display at Lucasfilm and ILM’s San Francisco Headquarters.

A graduate of the California Institute of the Arts, Blalack was among the first recruited by visual effects supervisor John Dykstra in the summer of 1975. Known as Robbie by most of his colleagues, he helped recruit others to the growing Star Wars crew, most of whom, like Blalack, were under 30 years of age. Among these was animation supervisor Adam Beckett. Another Cal Arts alumnus was optical printer operator David Berry, who remembers Blalack:

“I first met Robbie in 1971 at CalArts. Although we did not really socialize much, the film school was small and you knew who everyone was and what they were up to. We had a lot of mutual friends, including Adam Beckett. Beckett, Blalack, and Pat O’Neill were the kings of the optical printer. Pat O’Neill was our teacher and mentor. Blalack was pretty focused back then, and he could be intimidating if you rubbed him the wrong way. He did not suffer fools gladly. After he left CalArts, he managed to purchase a non-functional optical printer that was donated to the school (it was a custom job that was used on the film Marooned). Robbie got it working and established his business “Praxis” (along with Bruce Green, another “CalArtian”).

“The Praxis printer was eventually used to do all the ILM composites on Star Wars (after a lot of modifications),” Berry continues. “Although I knew Robbie, and knew he was doing the opticals for Star Wars, I was much closer to Adam Beckett, and it was through Beckett that I was able to get an interview with John Dykstra, and get hired to work in the rotoscope department. Eventually, Robbie invited me to work in the optical department for the final six months. He was a good leader and he really stood up for everyone in optical. He was open to suggestions and he always solicited our input. He must’ve been under intense pressure, I can only imagine, but he held up well. He was totally committed to Star Wars. And, he set me on my career path, and I am grateful that I got to express that to him.”

Along with crew members like John Dykstra and first cameraman Richard Edlund, Blalack led efforts to modify and retool ILM’s optical equipment to run the fabled VistaVision film format the company had elected to use for Star Wars. The establishment of ILM’s first visual effects pipeline required over a year of extensive work, and posed numerous unexpected technical challenges. By the time the pipeline was ready, ILM had only seven months to complete more than 300 effects shots.

Bruce Nicholson, who’d been recruited as an optical camera assistant on Star Wars, remembers that “at the time, ILM was struggling to get the visual effects done for the movie; they were way behind schedule. A ‘big push’ was initiated and I was brought on to help get the work done. I was originally offered six weeks of work that turned into six months. Robbie was under a lot of pressure, yet maintained his dry sense of humor despite it all. He had set up the compositing pipeline to handle the visual effects shots, most of which had to go through optical for completion.

“In the traditional era,” Nicholson continues, “compositing was a very complicated and byzantine process, with multiple film elements required for every layer in a shot. It was easy to lose track of shot flow, but Robbie’s system and the help of a couple of coordinators helped keep everything on track. I got along well with Robbie; I admired his fortitude and persistence. We were around the same age, and I felt more comfortable working with him than with the old timers I had worked with previously. He combined artistry and technical knowhow – the main qualities needed for success in visual effects.”

Along with his colleagues John Dykstra, Grant McCune, John Stears, and Richard Edlund, Robert Blalack accepted the Oscar for Best Visual Effects at the 50th Academy Awards in 1978. Having briefly added to the remarks on the television broadcast, Blalack sent his optical crew a Mailgram the next morning. “I forgot my lines on TV,” he told them. “I wanted to say: thank you to the women and men of the optical [crew]. Your dedicated work allows me to stand here tonight. This is our Oscar.”

Blalack’s work not only helped ensure the success of Star Wars: A New Hope and the dazzling effects that contributed to a growing Renaissance in the film industry, but also set the standard for ILM’s ongoing work in optical compositing, which continued to garner Oscar wins for new supervisors like Nicholson and Berry.

In 2021, Blalack penned a narrative about ILM’s odyssey to realize the visuals for Star Wars. Writing in the present tense, he recalled attending a public screening at Mann’s Chinese Theater during the first week of the movie’s release:

“The lights go out,” he wrote. “The Fox logo appears. The Lucasfilm logo. ‘A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…’ John Williams’ first notes blast. But louder is the roar of cheering and applause for the words Star Wars. The audience keeps screaming and applauding as the Star Destroyer moves endlessly overhead. Shot 101, as I know it, blows open the doors of perception, takes the audience into the cosmos where they dream and points to a universe limited only by the desire to adventure deeper into unseen arenas of the imagination.”