History in Objects: “Indy & Me”

George Lucas Himself Introduced Audiences to a New Indiana Jones Adventure

One of Lucasfilm’s first major forays into series television, The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles first broadcast on American screens thirty years ago this week on March 4, 1992. It was a Wednesday evening when the premiere episode, “The Curse of the Jackal,” aired at 8:00 PM on ABC.

That week, the publication TV Guide sported the 10-year-old Indy (Corey Carrier) on its cover. As the image of the young adventurer filled millions of American mailboxes, TV Guide readers were treated to a rare statement from executive producer George Lucas himself about the new Lucasfilm series and why he’d set out to make it.

In the piece titled “Indy & Me,” Lucas discussed his roots with television. At the age of 10 in the mid-1950s, his family had acquired a TV set, and the young Lucas soon discovered syndicated adventure serials that would help inspire both the Indiana Jones and Star Wars film series. As a young college student, Lucas was then influenced by anthropology and studies of other cultures, religions, and philosophies. These interests synthetized into the adventurer-archaeologist first played by Harrison Ford in Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981).

For the new television series, “I had to go backward and create a history that filled in the blanks,” Lucas wrote. “I had to show how Young Indy evolved into the Harrison Ford character.” With Indy’s father an academic, Lucas could send the boy on “exciting adventures” around the world while the elder Jones conducted lectures. Indy encountered historic figures from T. E. Lawrence to Pablo Picasso. “My daughters have been with me for many of my trips,” said Lucas. “Exactly what effect all this will have on their lives I don’t know, but in the end, they’re typical kids. I wanted that to be true of Indy, too.”

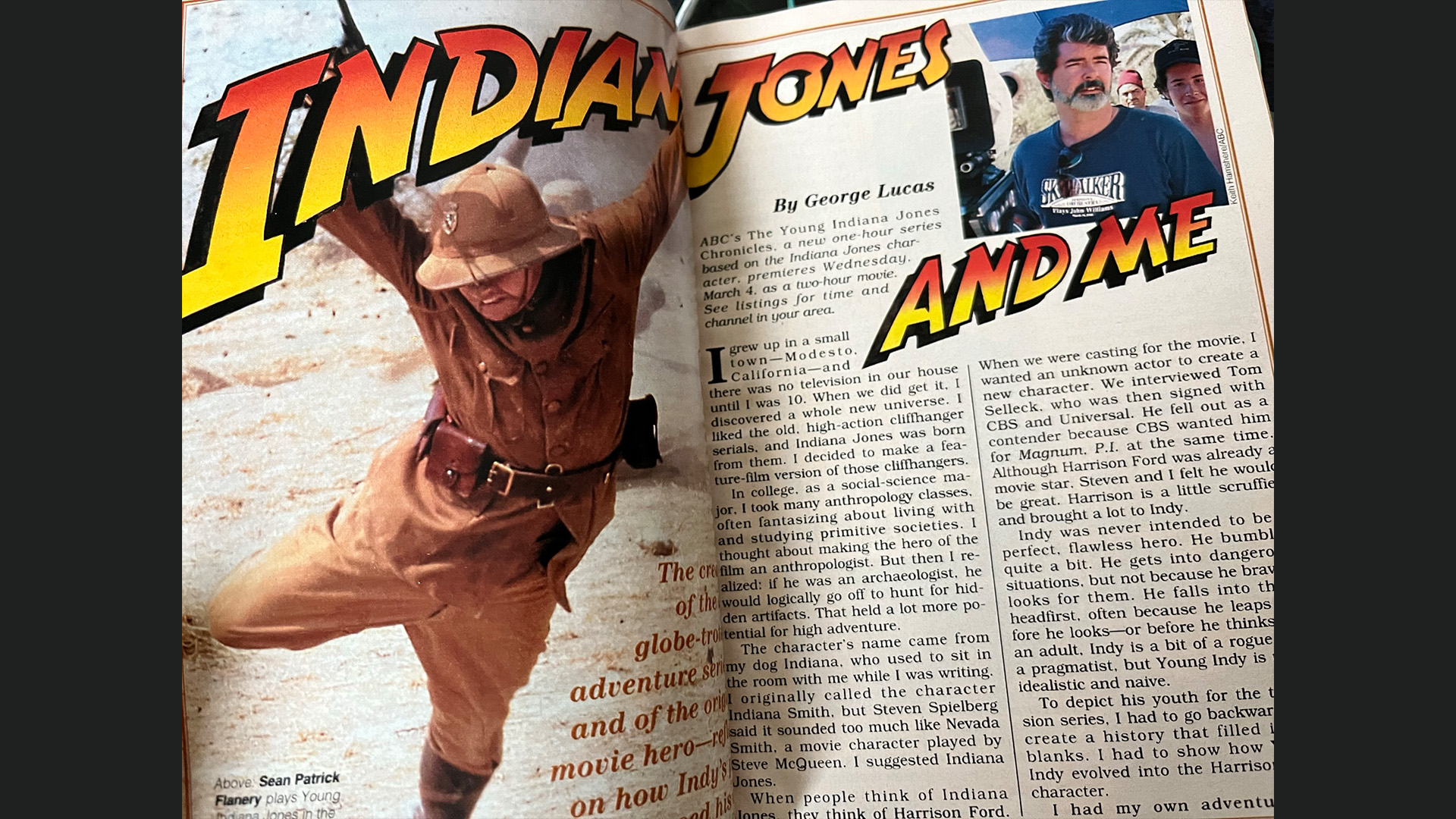

From boyhood through to his teenage years (when the older Sean Patrick Flanery assumed the role), Indy’s experiences reflected George Lucas’ interests. He’d encounter artists and thinkers, soldiers and statesmen, who collectively influenced the course of events in the early 20th century.

“It’s always exciting to watch Indy grow up,” Lucas said, “his life is exciting and intense. But for me, life is better when it is quieter.” Perhaps bringing Young Indy to the television screen was a way for everyone, regardless of their ability for world travel, to embark on an adventure of the mind.

Rightfully, Lucas focused on the story and themes behind Young Indy in his brief essay. But he hadn’t mentioned that, in making the series, he was also thinking ahead to future Lucasfilm stories. A globe-trotting production that shot year-round, Young Indy’s post-production was centered at Skywalker Ranch where Lucasfilm’s state-of-the-art EditDroid and SoundDroid digital tools were used. The company had spent more than a decade creating them, and Lucas was eager to test out new computer-based means of filmmaking. These advancements would continue with Radioland Murders (1994) and ultimately, on the new Star Wars prequel trilogy.