From Morphs to Magic Bolts: ILM’s Mark Bakowski on Willow

The visual effects supervisor shares some behind-the-scenes tricks used to create Willow’s world.

Although George Lucas and Ron Howard had discussed concepts for a Willow television series at different times over the years, the catalyst for the series that Lucasfilm ultimately produced came during production of Solo: A Star Wars Story (2018). When Howard joined that project as director, co-writer Jonathan Kasdan began lobbying for a revival, and the rest, as the saying goes, is history.

Elsewhere on the Solo set was Mark Bakowski, working for Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) as an additional onset visual effects supervisor. He’d join ILM’s London studio around the time of its establishment in 2014, having spent many years in the visual effects industry of his native England. At ILM, Bakowski has “grown and grown ever since,” as he tells Lucasfilm.com, working as visual effects supervisor for projects like Spectre (2015), Aladdin (2019), The Midnight Sky (2020), and No Time to Die (2021).

Willow presented a mix of new opportunities for Bakowski. Not only would he be stepping into episodic television, but into the role of Lucasfilm’s visual effects supervisor overseeing the entire series, including work accomplished by ILM and partnering vendors. This was distinct from his previous roles working with clients within ILM on specific assignments. “As a visual effects supervisor with ILM,” he explains, “a client will come to you with a particular request like a creature or a sequence. Your job is to execute it well, and you bring ideas to it, and that’s fun.

“But working as the head of department is so much more interesting,” he continues. “You’re watching the script evolve as it’s written and rewritten. Problems come up, things happen, and you have all these discussions about what’s feasible. You’re part of the evolution of bouncing creative ideas off each other to find solutions. You can have a lot more creative input. It’s problem-solving, not just on the pixels level, but rather along so many fronts. The reason a lot of us go into this industry is because we love movies, that’s what it’s all about for me. This brings you closer to the feeling of being a filmmaker, being involved, and putting your stamp on it.”

If loving movies is what it’s all about, then Bakowksi was particularly excited to be involved in a project with such lineage. “You’re obviously a fan of the original Willow if you like visual effects,” he says. “Everyone remembers it.” The team was even able to incorporate a handful of morphing effects into the new series, modern equivalents to the groundbreaking transformation of Fin Raziel created by ILM’s burgeoning computer graphics team in the late 1980s.

Examples of morphs from the new series include the Dag’s transformation from a bird into humanoid form, and later when the Withered Crone is finally revealed in her true, hideous appearance. As the original ILM team had originally shot practical elements for Fin Raziel, Bakowski and his crew onset helped shoot with the Dag (played by Claudia Hughes). “We wanted her to have forward momentum, so we asked to have her standing on a box so she could jump off it and move forward as if she were coming to a stop,” he says. “The camera operators also needed to be aware of the size of the bird. The tilt-down needed to allow space for it to occupy. We’d show the crew the pre-visualization to help suggest the idea.”

In his capacity as overall effects supervisor, Bakowski was present for the entirety of Willow’s principal photography at Dragon Studios in Wales and on location around the country. This required many months away from his home in London, and enduring constant changes during the global pandemic. It also required constantly shifting from task to task with multiple episodes in simultaneous production. “You’re prepping one thing while they’re shooting something else in the middle,” says Bakowski. “It can get incredibly busy just trying to stay on top of things. You’re doing a recce at one place while they’re shooting a difficult scene in another place. You need a good team, and we had one.”

Among Bakowski’s team was onset visual effects supervisor Nicky Walsh, who remained attached to the show’s main unit. When a second unit was working, Bakowski would join them in the same capacity, but otherwise remained flexible to move from task to task, overseeing preparations across the entire shoot. By far the biggest logistical challenge was navigating the pandemic. At one point, Willow’s entire effects team came down with COVID-19, save one trainee who stepped up to fulfill the team’s role while filming continued.

Many different techniques would be employed on Willow, what Bakowski describes as an “old school” production that incorporated the latest tools (like de-aging for a younger Willow, accomplished by the Irish vendor Screen Scene) and tried-and-true practical approaches. They did not incorporate ILM’s elaborate StageCraft Volume onset, but instead utilized more traditional and often quite ingenious tricks.

“In episode seven when they’re on the Shattered Sea, there’s a giant sunset,” Bakowski explains. “If we did it on greenscreen, it would’ve been very expensive. So it’s actually a big trans light, basically a big picture in the background that was illuminated in different ways. ILM made one large picture of a sunset and the director of photography [Will Baldy] could put cool or warm lights behind it to change the vibe. Then in post-production we’d do a few little extensions, but in some angles, it already lined up perfectly. We’d add some extra lens flare to the sun, move the clouds, and put some birds in to give it life. It’s not the Volume, it’s just a big picture!”

Bakowski admits that “it was a leap of faith to say we could do it, but I think it’s justified. It feels in the spirit of the original Willow. It’s physical and real, and similar to a Volume, but people could actually see it.” For the moments at night on the Shattered Sea, a similar background lighting pattern was used, only much darker, and the effects team later added the magnificent stars and reflections.

“Beyond the Shattered Sea” also included scenes where Graydon interacts with his newfound companion, a Mudmander creature whom he names Kenneth. “When Graydon gives Kenneth a pat on the head, that’s an animatronic created by Neal Scanlon’s team,” Bakowski notes, “but we often replaced elements of his face, like his eyes and nose. It’s a hand in hand collaboration. We just needed to help make sure the pupils dilated and add some of those details.”

The shots of Kenneth pulling the watercraft across the Shattered Sea required ILM to replace practical tools and elements from the shoot like the tow-vehicle, tracks in the mud, and distant scenery. “Those scenes work quite well,” says Bakowski. “They’re really on a beach being pulled with the wind in their hair and the lighting. It fits that logic of trying to do things for real and filling in the visual effects around it. You get that natural, physical vibe.”

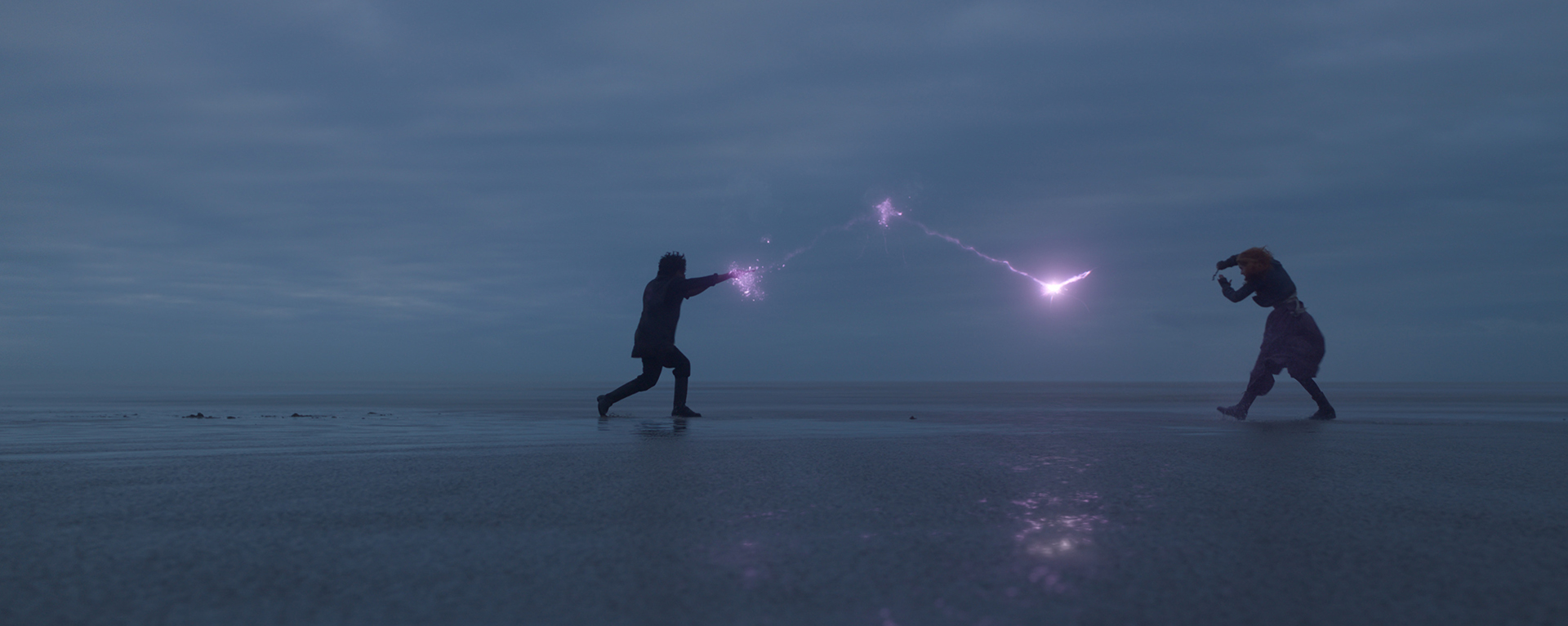

Bakowksi notes that there’s a “physicality” to the overall approach of Willow’s visual effects. “We were shooting in muddy fields and beaches,” he says. “There is greenscreen and CG work, but there’s an earthy feel. We try to keep things as grounded as possible in a world where people are throwing magic bolts at each other.”

The crew had long discussions with showrunner Jonathan Kasdan about the magic, in particular. “Jon was always mentioning the idea of tapping into the magic of the universe,” Bakowski says. “It’s an idea that’s it all there, just hidden. There’s magic everywhere.” For the elaborate duels in the final two episodes, they captured the sequences in “broad strokes,” using the appropriate colored lights (green for good, red for bad), then working in post-production to refine the actual bolts of energy.

“We told Jon that we needed a reason for the magic to stay in the air,” Bakowski explains. “One character might hold their hand out, and the other doesn’t hit the ground immediately—does the magic bolt take a strange path to get there? We had to justify these kinds of things with logic. We imagined there are lay lines in the air, like a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle. Magic can bounce around between these lay lines. It doesn’t go directly from A to B. It zigzags, it can split in two. This logic allowed us to control the speed and timing.

“Some of the flashes are random,” he continues. “There’s a crackle like St. Elmo’s fire in the air. There’s so much energy that it creates a little firework display. It was retro-fitted, but we worked that out as a group. Everyone was wary of it looking too much like the Harry Potter movies. I think it’s different. By the end you have the characters grappling on multiple planes, almost like two octopi having a game of Mercy, pulling against each other.”

Throughout his experience on Willow, Bakowski appreciated Kasdan’s commitment to world-building. They were always asking questions like, “what can we put in the background here?” (Kasdan devised the idea for Andowyne’s two moons in this fashion.) In “Beyond the Shattered Sea,” Bakowski explains that “there’s one shot where they see a giant skeleton in the water. I’m always keen on having something there that no one comments on, if that makes sense. To me it’s more interesting if they don’t say something. That makes it normal.” The final result is akin to C-3PO’s shuffling past the unexplained Krayt Dragon skeleton in Star Wars: A New Hope (1977).

Reflecting on a long shoot with physical demands that “tested everyone,” Bakowski notes that “there was a real team spirit that carried us through.” The most rewarding part of the experience was forming bonds with his colleagues, whom he’d love to work with again. As he says, “Who you work with is the most important thing.”

—