Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom with ILM’s Dennis Muren

The Visual Effects Legend Reflects 35 Years Later

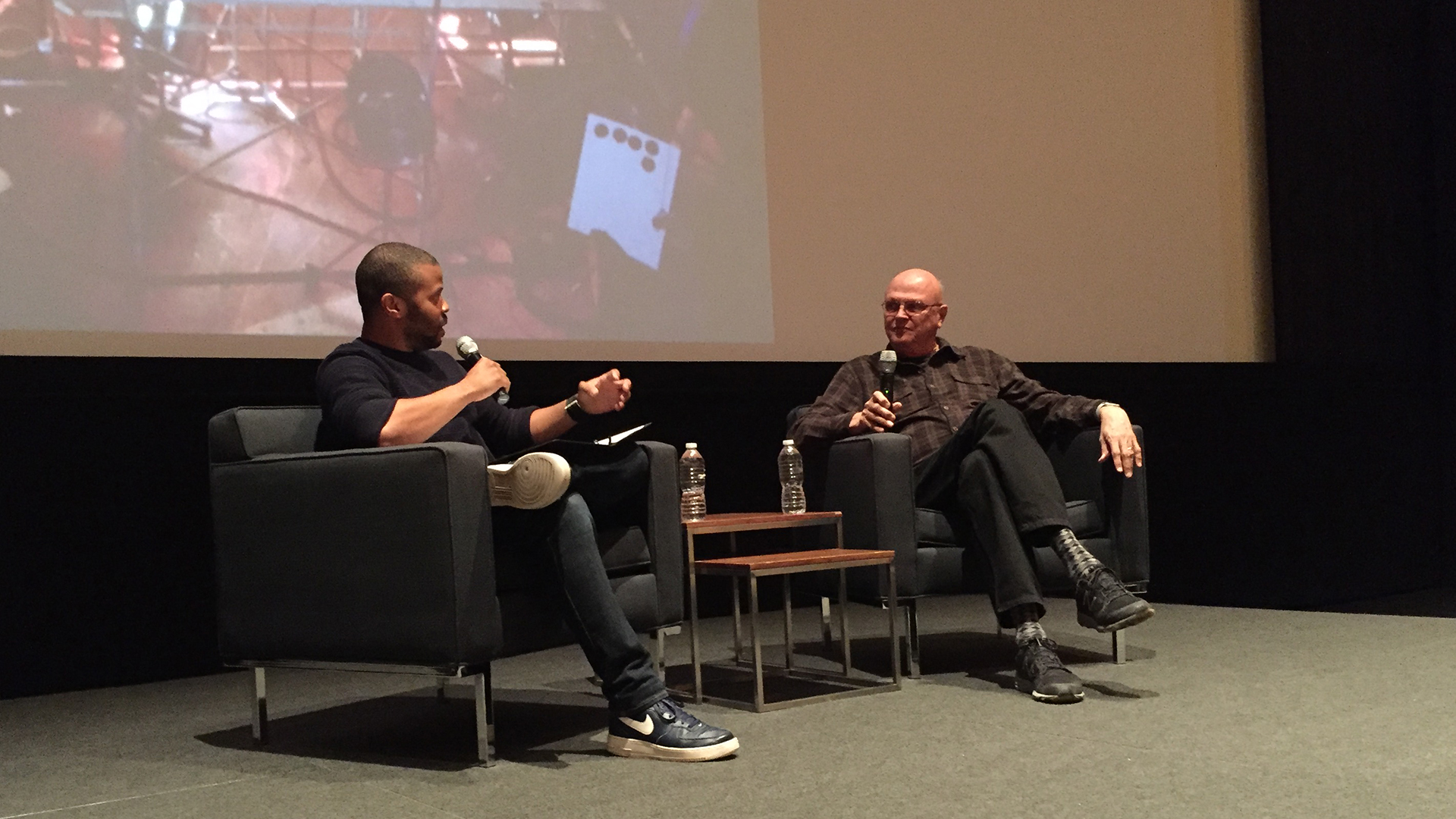

Employees from Lucasfilm and Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) recently gathered at our San Francisco campus for a 35th anniversary presentation of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom followed by a conversation with Visual Effects Supervisor Dennis Muren, moderated by ILMxLAB’s Justin Bolger.

Muren won an Academy Award for his work on Temple of Doom with fellow ILM crew members Mike McAlister and Lorne Peterson, along with Mechanical Effects Supervisor George Gibbs.

Now 35 years later, Muren commented that in a Steven Spielberg film, “everything is shot in an exaggerated way. The sets are like that, the acting is that way, and I thought the effects should be too. They don’t call attention to themselves, but it makes the audience think, ‘Wow that’s more than I thought I would’ve seen!’”

Muren recalled Doom’s towering chasm model constructed for the scenes where helpless victims are lowered into the lava stream below. The ILM artists wanted “active lava,” as Muren put it, which flowed steadily and could be manipulated to create whirlpools. A combined liquid of methyl cellulose and water was lit from below for a mesmerizing view.

The model chasm stretched to the ceiling of ILM’s main stage. Muren was positioned at the very top alongside the camera. “One of the great things about ILM at the time,” he recalled, “was that all of our stage guys had worked at the opera house and all the theaters in San Francisco. So they were used to working 40 feet in the air. I was scared to death up there!”

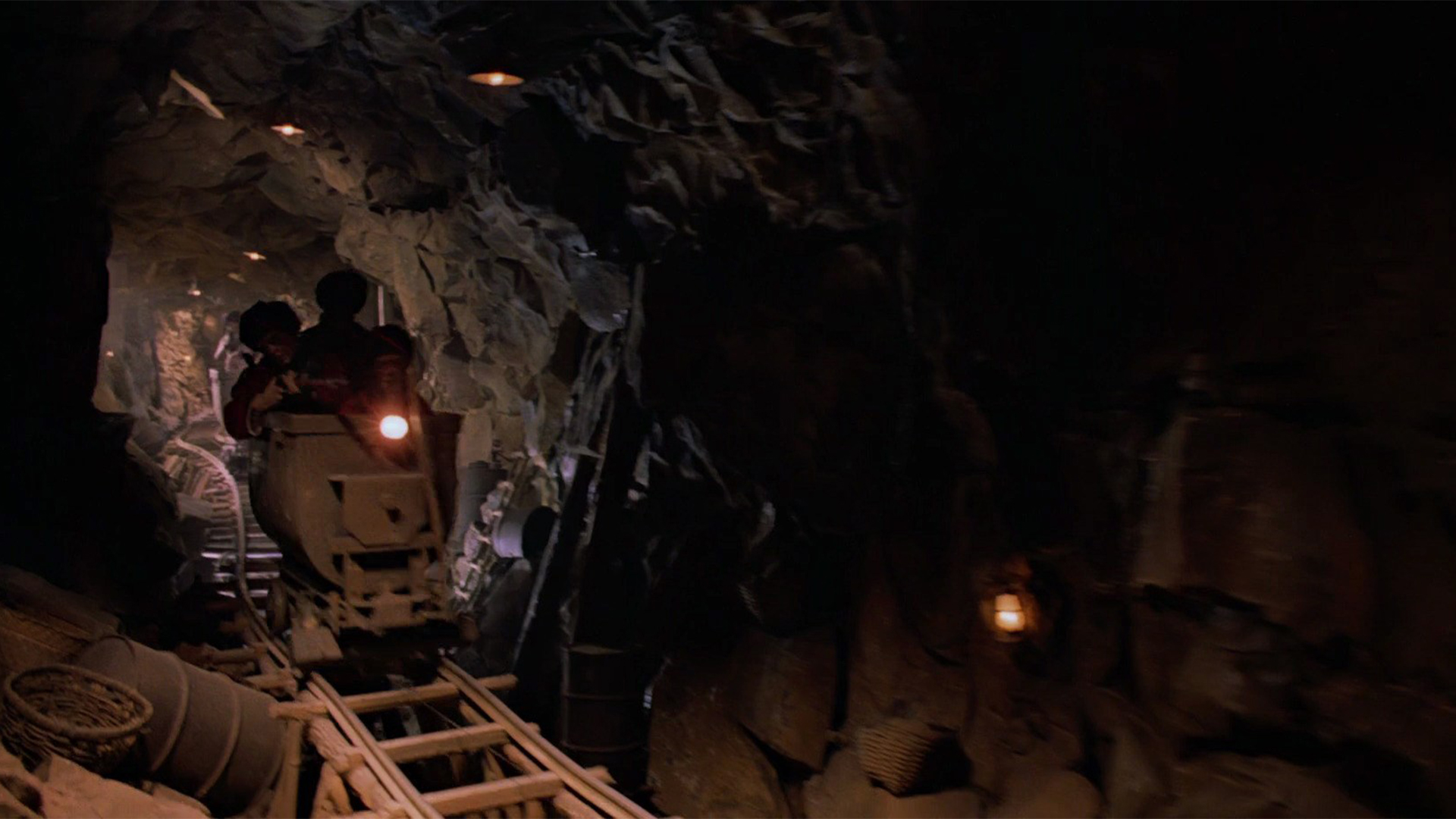

The fabled mine cart sequence where Indy and friends are pursued in a high-speed chase was one of the most cleverly-executed sequences yet accomplished at ILM. Muren joined cameraman Mike McAlister in crafting a solution to ILM’s limited stage space and tight budget.

With little choice but to erect a substantially-detailed and expansive model, Muren went back to the “first principle,” which was the simple fact that their usual camera was too big for any other kind of space. “So I thought, ‘Why can’t we do it with a still camera?’”

They settled on a small Nikon camera, reconfigured to take 35mm film. With the set then reduced in size, the model shop crew had the idea of using tin foil to create rockwork. “You could build it with a tinker toy set,” Muren commented. “It was flexible and easy to use.” The camera rolled down the narrow mine track, filming in stop motion with animated human figures.

“What matters is what’s on the film, not the process,” Muren explained. “So I didn’t care how crummy the set was, I actually like that, because that’s where the magic part came in. I’m sure people touring the set at the time thought it was the most rinky-dink thing they’d ever seen.”