Magic Show: The Visual Effects Wizardry of Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny

Production visual effects supervisor Andrew Whitehurst speaks to Lucasfilm.com about the summer blockbuster’s biggest sequences.

Spoiler warning: This article discusses story details and plot points of Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny.

“I’ve been looking for this all my life,” says our adventuring archaeologist in the trailer for Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny. But that sentiment could have also come from Industrial Light & Magic’s Andrew Whitehurst, longtime visual effects supervisor, about what the opportunity to work on the film represented.

“I have the joy-of-going-to-the movies side of loving Indiana Jones, which was that it was this ultra-exciting adventure serial,” he tells Lucasfilm.com. “Everything seemed plausible and tangible and real-world, but then with this supernatural edge to it. The characters were so engaging and there never seemed to be anything cynical about it. The peril is absolutely in earnest and the jokes are absolutely in earnest. Even as a kid, I loved that. And from the visual effects side of it, in the ‘80s there was a BBC science series called Horizon. Every week they would do an episode on a different subject, and one week they did visual effects, which I knew nothing about. I was nine years old, and it was mainly focused around the making of Temple of Doom. And so I had my mind blown for an hour where I learned that you could make movies with models and paintings and animation. That was my literal introduction to what visual effects is. To see that and, you know, 40 years later I’m supervising the fifth one, it’s kind of crazy. So, the visual effects of Indiana Jones is a really key component in me doing what I do for a living now.”

The adventure begins

As production visual effects supervisor on Dial of Destiny, Whitehurst would oversee the work of ILM and all vendors for a time and world-jumping adventure, which follows Indy from WWII-era Europe to 1969 New York and Morocco to ancient Sicily. Even for someone with Skyfall, Ex Machina, and Annihilation on his resume, it was a lot. “The trickiest thing about a movie like this is that it’s an odyssey,” he says. “Almost every single scene is in a different location or has a different component to it. So you have to break up the project into all of the various places that we are and things that happen within those places.” Whitehurst worked closely with production designer Adam Stockhausen in figuring out the look of the various effects sequences in the movie, with input from director James Mangold throughout the process.

Over time, Whitehurst has developed his own method for realizing sequences in a way that welcomes in his collaborators. “My background is in fine arts, so I tend to draw and paint a lot for two reasons. One, for me to start to get my own head around how things might look or the things that are going to be tricky. And also, then, to communicate ‘How about doing things this way?’ to Jim or Adam or, Phedon Papamichael the DP, or Mike McCusker the editor, and so that they’ve got something concrete in front of them as a drawing or as a really rough, sketchy animatic or a painting or something. They go, ‘Well, I like this. I don’t like that. What about doing this?’ I tried to get things going visually as early as possible, often in quite a rough, loose way.”

As a fan of the original Indy movies, Whitehurst was well aware of their visual style. The gritty feel, stunts, the real-world quality, all augmented by ILM’s most cutting-edge effects techniques of the day. It was important to him that Dial of Destiny honor that legacy while still allowing for creative freedom. “You definitely have to be respectful. Looking at the previous films, the way [cinematographer] Douglas Slocombe shot the first three has a very certain look to it. And I don’t think that’s necessarily what Phedon and Jim were shooting for when they were coming up with a visual style for this film. But again, particularly in the opening sequence, because it does have that more historical aspect to it, we were certainly riffing on those ideas,” he says. “I think it’s more being respectful towards the ethos of the movies rather than a very particular aesthetic.” Still, Whitehurst did take steps to ensure a certain visual continuity. “All of our cameras are grounded in reality. Even if it’s a full CG shot, I will sit down with an artist and go, ‘Well, look, if we were going to shoot this for real, it would be a camera on a stabilized head on a crane arm attached to a car. So when we’re animating the camera, we can’t do some super smooth, flying through space kind of camera move because that’s not part of this world.’ And it’s that kind of aspect of grounding things that I think was really important for us to respect. But then also, the franchise has always had this wonderful, magical, slightly fantastical element of the supernatural aspect, which happens within them. And so that gives you a little bit more license to play.”

The adventures of young(er) Indiana Jones

Dial of Destiny opens in 1944 during World War II, with Indy and friend Basil Shaw trying to recover stolen art and artifacts from fleeing Nazis. The sequence — a significant chunk of the movie — moves from an occupied town in Europe to a moving train, and stands on the shoulders of some ILM wizardry: throughout, it features a de-aged Harrison Ford, appearing as Indy would’ve in his mid-40s. But going into production, it was still a question mark as to how they would pull it off. “That was something that grew,” he says. “And obviously it was the biggest unknown in terms of what technology we are going to use. ‘How are we going to make this work? How are we going to shoot it?’ So we were doing a lot of technical tests, working directly with Harrison Ford, to see what sort of de-aging techniques we might use.”

The train portion of the sequence would require Indy to walk, jump, leap, and fight both inside and on top of the train. It was partially inspired by the films of Buster Keaton, according to Whitehurst, which gave him an idea of tone — balancing action with humor — while figuring out how best to accomplish the de-aging. “We were kind of going a hundred miles an hour in creative experimentation and technical experimentation. And I remember, one of the first conversations that Jim and I had about this, and he said, ‘Well, how are we gonna do this? What techniques are we gonna use?’ And I said, ‘All of them.’” That would mean ILM’s FaceSwap toolset would be used, which incorporates onset data, traditional reference material, archival footage, digital painting and animation, a full CG head, and even some machine learning to swap the face for an alternate that’s more scene-appropriate. For Whitehurst, there was an important reason not to rely on only one method.

“If you do a magic trick the same way eight times in a row, people will start to spot the trick. They’ll see what the slight of hand is. Whereas if you do it once in a slightly different way, and then in the next shot you do it a different way, it keeps things fresh.” Even dailies had a rudimentary face replacement effect baked in, which gave the filmmakers an idea of what the final sequence would look like, and allowed ILM to see which method might work best depending on movement, lighting, or camera placement. “That’s our ground zero,” Whitehurst says. “Now how do we make it cinema quality? And that was, as I say, why we used every single technique.”

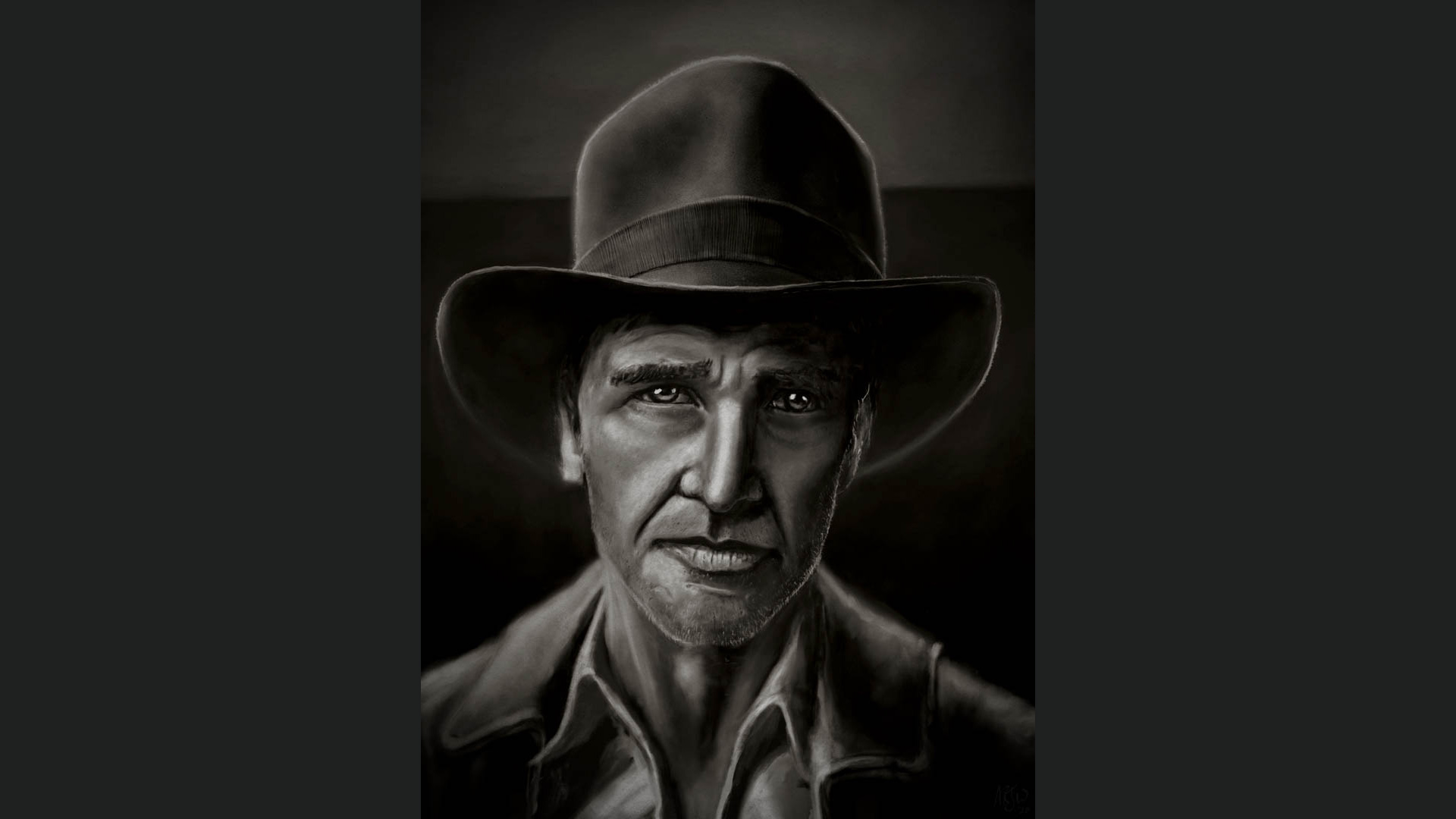

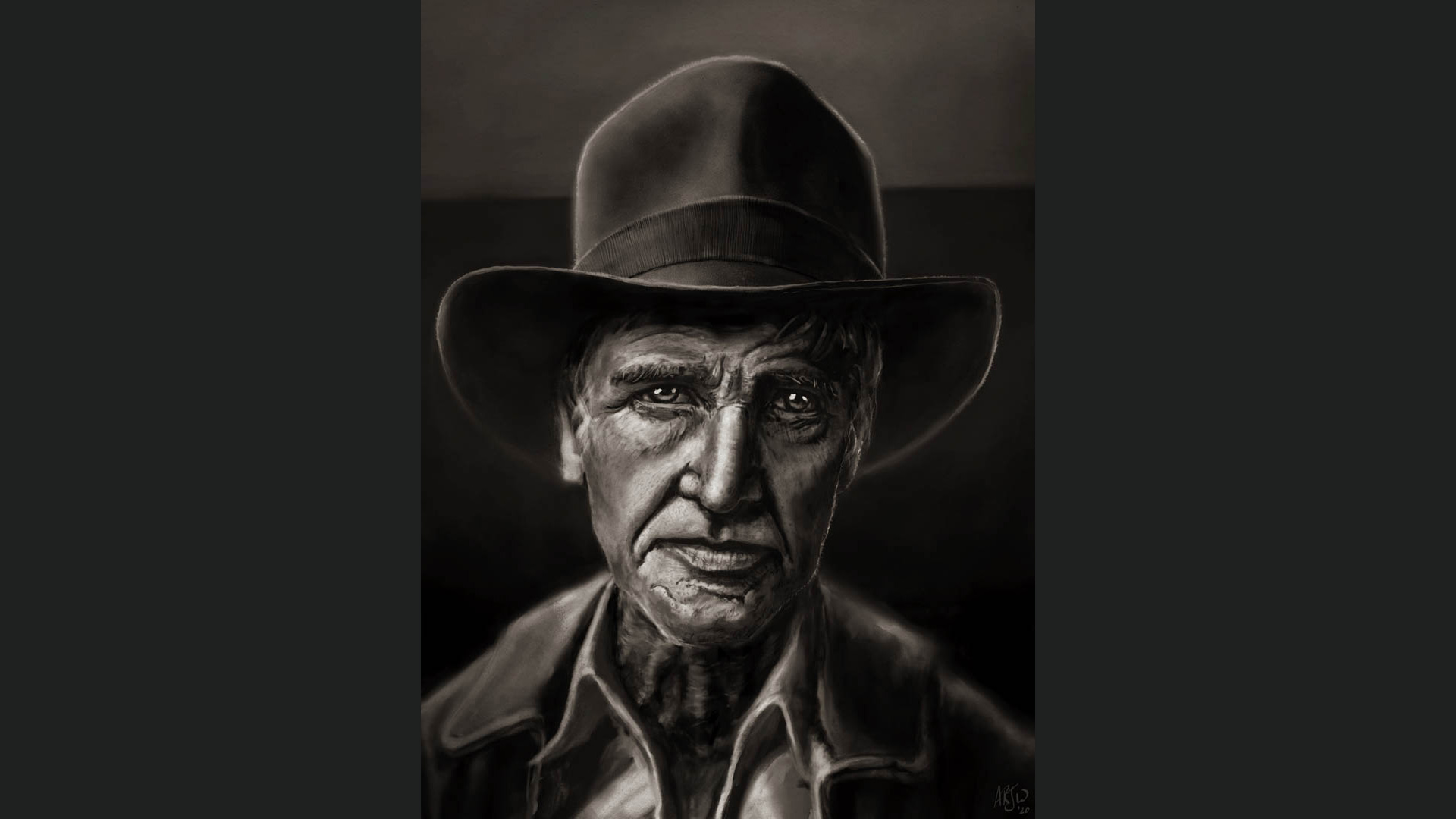

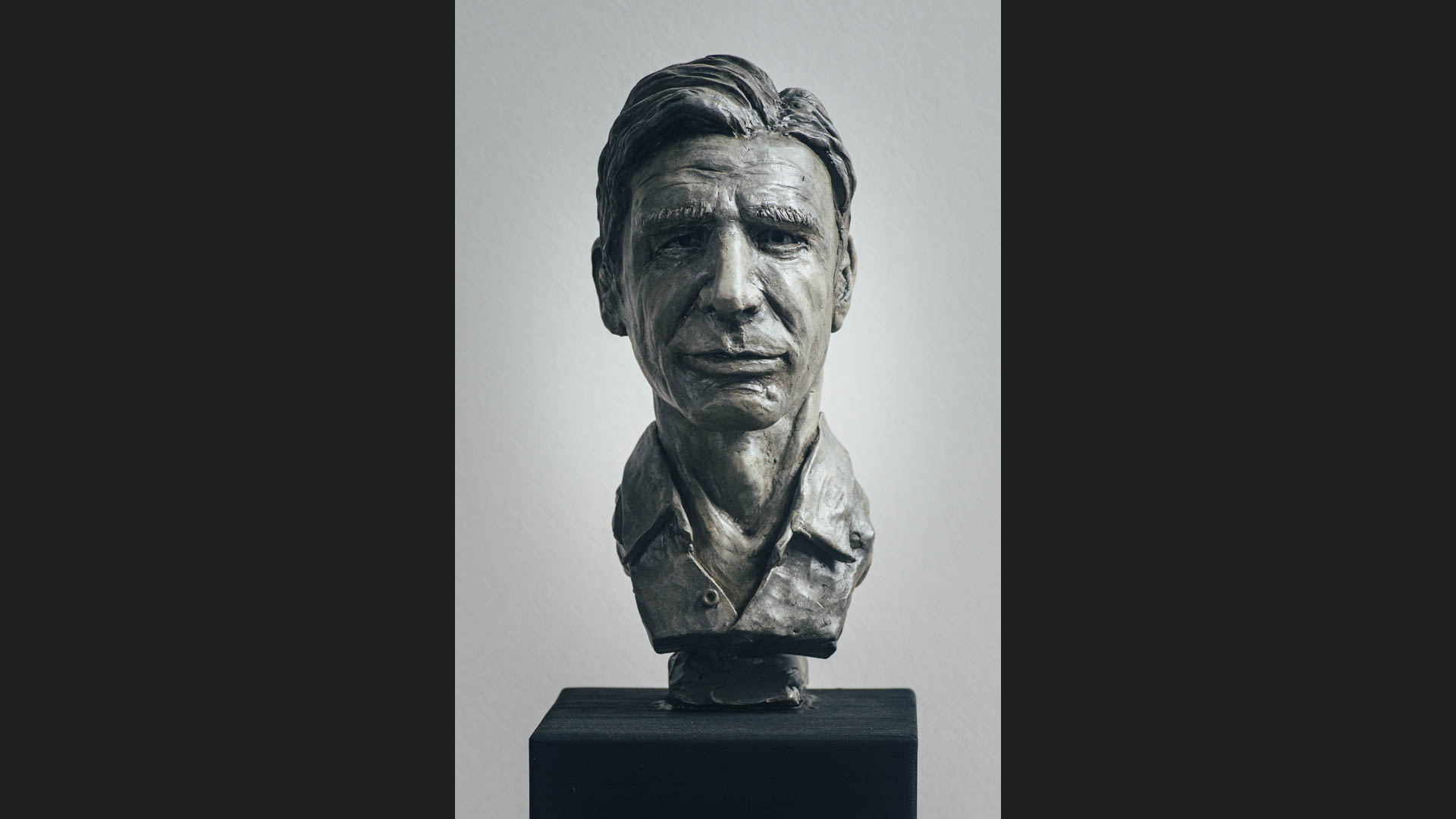

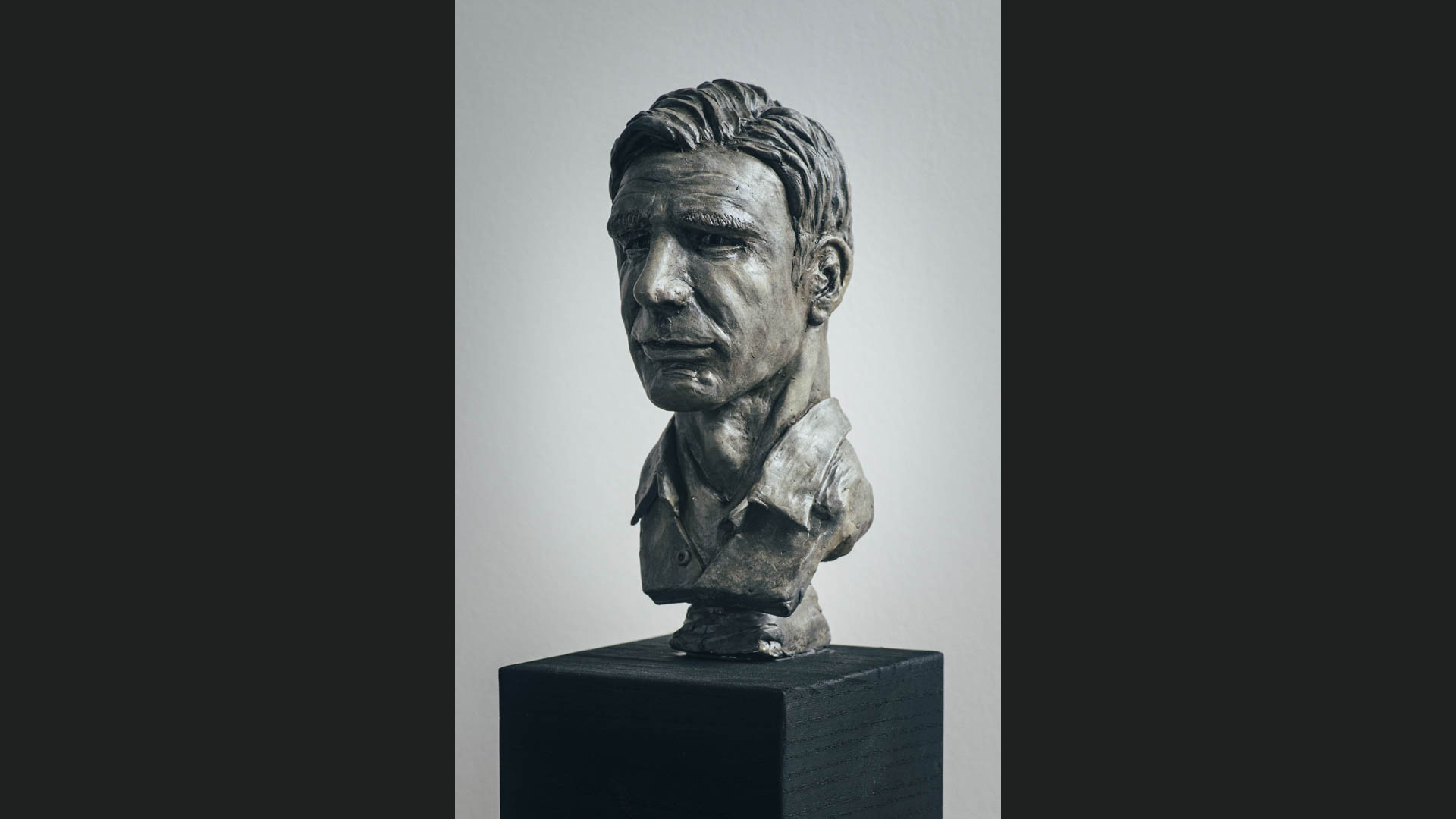

In working on the sequence, Whitehurst became something of a Harrison Ford facial expression expert. He painted portraits of Ford to become familiar with the contours and quirks of his face, and also sculpted a maquette of the actor. He also put Lucasfilm’s resources and history with Ford to use. “One of the first things I did was, I went through the first three Indiana Jones films. I made my own document of time codes — what shot it was, whether it was close up or front three-quarter, what the lighting direction was, and what the type of performance was. You know, like, angry, happy, conversational, whatever. And I made those lists, and then I handed those over to Lucasfilm and said, ‘We would like these at 4K, thank you very much.’ For a lot of them, they actually had the scans already from when they’d done previous restorations for Blu-ray releases or whatever. And other bits they went and pulled for us. So that was something that we could then start incorporating into our FaceSwap process as reference material.” Having all that footage, documented and organized, served other purposes, as well. “It gave us, as artists, a library of what Harrison looks like. This is how Harrison moves his face. This is how he smiles. This is how he grimaces,” he says. “By having this reference material readily on hand, it made that job much easier for all of us involved. Because we could literally point at this shot from this movie and go, ‘Well, look at that. That’s basically what we’re shooting for here and we haven’t quite got that yet.’ So all of the source material was used directly in developing the final look of Indiana Jones, and it was also massively useful for both artist reference and for me.”

While accomplishing an effect like this is a hurdle, there’s another challenge that comes with this kind of work: knowing when to stop. “You could continue to refine things for forever. And one of the reasons why you could continue to refine things for forever is because there isn’t one single objective truth that is out there. I mean, people look different day to day,” Whitehurst says. “You absolutely can drive yourself completely and utterly crazy.” To ground the team in these situations, they would always return to reference images and the very first FaceSwap image picked for a given shot, examining why they liked it over other options. “Let’s just back up.”

And what of Indy himself? For his part, Ford was enthusiastic about the de-aging from the get-go and a willing partner. “He saw some of the very early tests, which he was very encouraged by,” Whitehurst says. “And then once we were in the edit, he certainly came and watched the movie and there were, you know, bits we go, ‘I’m not sure about that,’ or ‘I really like this bit,’ or we would get the notes back and we would go, ‘Okay,’ and work accordingly. He was intimately involved, both in driving the physical performance and developing the look.” Indeed, Whitehurst confirms Ford performed much of the on-screen action during the train sequence, mo-cap dots on face and all. “As much as possible, it’s Harrison Ford. It turns out he’s extremely good at playing Indiana Jones,” he quips. “We felt we were onto a winner with that guy.”

Turning back the dial

For Dial of Destiny’s climax, Nazi scientist Jürgen Voller uses the titular device to travel back in time. Except instead of WWII-era Germany as intended, he, Indy, and others end up at the Siege of Syracuse — the Roman invasion of Sicily in 212 BC. Much of the shooting would take place on location in Sicily and some at Pinewood Studios in the UK; Whitehurst, having worked on the movie Troy, was well experienced in bringing this era of history to life and was eager to do so again. “Any questions you’ve got on ancient Greek naval architecture, I have a pretty passible working knowledge of a trireme,” he says. “And for the city, we did our research. What were ancient Greek houses [like]? How did they lay their cities out? So it has that reality to it.”

Whitehurst and ILM also got to play city planner. Just like their approach in recreating 1969 New York for the film’s middle act, Whitehurst wanted Syracuse to feel like it was home to a populace, i.e., not pristine and not perfect. “When I was talking to Robert Weaver and his ILM team about it, I said, ‘Well, look, we have New York City in 1969. It feels lived in and it’s got signs that are busted up and there’s rubbish in the streets and all of that. We need to do the same thing, but for 200 and a bit BC, Syracuse. It needs to feel like a real living city. I want the roads to be sensible and the city blocks to be sensible,’” he says. “And so we knew that that was how we were going to conceptually build the city. At the same time, we have our narrative as to what’s happening in the plane, who are we following, what’s happening where.”

In the end, they developed a functional Syracuse, designed to be realistic but also serve the on-screen action. “We worked out that we were going to need to have a big inlet that the plane flew down before it banked over the city, literally because this was the narrative order that events were going to happen in. I spent a lot of time working with Clint Reagan, the pre-viz and post-viz supe, figuring out what this city would actually look like to achieve all of the things that we needed it to in the order that they happen. Then once we got that, then we could hand that to ILM and go, ‘Right, okay. That’s now the layout of the city. That’s now the layout of the coastline.’” There were further tweaks, however, during post-production, as the sequence continued to evolve in editing. Whitehurst sees the completed climax as a testament to all the departments that came together to execute it as best they could. “The sequence was very fluid, and it did change a lot as we understood what it needed to be, which I think is to the credit of everybody working on it, because it was a really genuinely collaborative process.”

The final adventure

With Dial of Destiny now in theaters, Whitehurst’s own Indy adventure has come to a close. Looking back, there are some visual effects that he’s particularly proud to have brought to the screen.

“I’m personally very fond of the cloud — the portal we see when we get to Syracuse. I kind of love the shape of that. It’s got these moody arms coming around, and it hopefully has a little bit of that [visual effects legend] Doug Trumbull-ness to it; like a giant cloud tank. And, you know, the whole New York sequence I just think looks great.” Whitehurst also points toward a smaller element of the larger final act as a favorite.

“One of the sequences that I always get a kick out of is when Helen was on the motorbike chasing the plane in the driving rain at night. That’s Phoebe [Waller-Bridge] on a bike in front of a blue screen and she let us blast wind and water at her all day long, like a trooper. And she’s awesome. I mean, she just totally sells it. We’ve got some shots in there, which were stunts, right on a motorbike on a real airfield,” he says. “But most of it is Phoebe against the blue screen and there’s some really super cool shots in there that I really love and, again, feels absolutely on point for the world of Indy.”

And as the world of Indy sparked Whitehurst’s interest in visual effects, Lucasfilm.com has one final question: Where does Dial of Destiny rank on his resume?

“Well, it’s got to be right up at the top there, hasn’t it?” Whitehurst says. “I mean, I’ve done a lot of movies, but none of the movies that I’ve worked on to date were a key part and fundamental part of my childhood. Indiana Jones, the fun, the excitement, the going to crazy places, the bravery, and just the general courage are so foundational and were so important to me growing up. But to be part of that is incredibly special.”

Dan Brooks is a writer and the senior editor of StarWars.com and Lucasfilm.com. Follow him on X at @dan_brooks and Instagram at @therealdanbrooks.